What it means to be Zimbabwean

What does it really mean to be Zimbabwean?

This is a question I’ve been reflecting on more and more since relocating to the diaspora. It’s not easy to answer, and I’m not going to pretend to have it figured out. Zimbabweans are proud, passionate, opinionated people. You can’t tell a Zimbabwean who they are—they’ll likely argue with you just for sport. So, this isn’t a declaration. It’s just my point of view. A lived one.

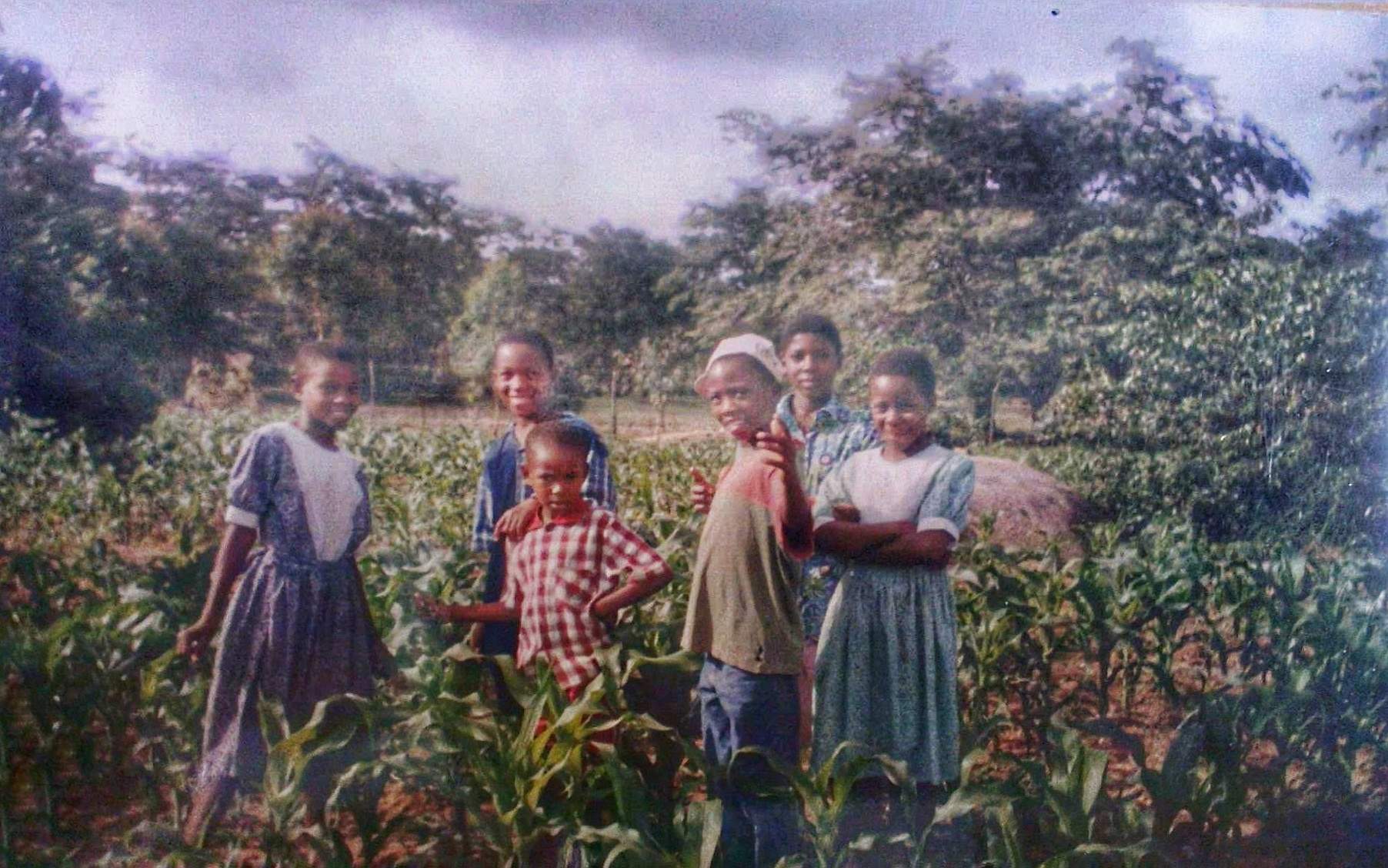

I grew up in community. Real community. A buzzing house in Milton Park filled with mothers, aunties, and kids who weren’t necessarily siblings but felt like family. There was no such thing as solitude—we shared food, laughter, and life. Even after I moved to Hwedza, that spirit of togetherness was always present. Holidays were sacred; a time for cousins, uncles, and aunties to descend on the homestead, filling it with stories, music, and warmth. In hard times—funerals, sickness, heartbreak—the family showed up. Our elders made sure that we leaned on each other, that we lived with and loved one another as we were. There was grace in that. Quiet strength. An unspoken contract that said: I am because we are.

But our pride can be a double-edged sword. We’re ashamed of failure, and failure in Zimbabwe doesn’t just stain the individual—it leaves a mark on the whole family. So we internalise. We wait for a break, suffer in silence, and re-emerge when we’re “together” again. I’ve never been afraid of failure or of asking for help. But I’ve tasted the bitter reactions that follow. The labels. The whispers. Growing up an orphan, the weight of societal judgment came early. There’s a quiet cruelty in the way we speak of children without parents: "nherera yanhingi,"—as if their very existence is a reminder of what was lost. And yet, in that same society, support is offered. It’s a strange contradiction: the same hands that hold you up are the ones that pinch your scars.

I used to say I’d never leave Zimbabwe. Come what may. But you get to a point where conviction alone can’t carry you. The system is broken. The leadership has failed to nurture the values that once held us together. The fish rots from the head. And so, like many others, I left. I crossed borders carrying more than just luggage—I carried memory, identity, and a lingering sense of loss.

Living in the diaspora is disorienting. You begin to conform, bit by bit, to your host nation’s culture. Even your palette adjusts. Suddenly, your favorite traditional dishes are luxuries—if you can find them at all. The shift is slow but sure, and before long, you’re a visitor in your own story. You start to understand what the old ones meant when they said kusina mai hakuendwe. Because leaving home means leaving the comfort, nurture, and clarity that only a mother—or a motherland—can provide.

Then there's the question of language. If I stop speaking Shona, do I stop being Zimbabwean? If a child grows up fluent in French or Arabic but has roots in Masvingo or Tsholotsho, where do they stand? I don’t have the answers. I just know that the erosion of language is one of the most silent yet dangerous losses we face. Colonisation didn’t just impose systems—it erased stories. We’re often taught that our history began in 1890, as if we were born in struggle and defined only by resistance. But we had empires. Knowledge systems. Spiritual beliefs. We had ourselves.

Yet even in this loss, there is resilience. Some have held the line. I think of the Nyaradzo Group and how they’ve preserved our traditions around mourning and remembrance. I think of the musicians who keep our hearts intact, translating pain into rhythm, joy into melody. I think of the grandmothers who still tell folktales under the stars. There’s something in us that refuses to die.

And so, my dream—my hope—is to start at the beginning. To document all the languages spoken in Zimbabwe. To give each one space. That, to me, is the real starting point. It creates a level playing field and offers every Zimbabwean a voice. It gives communities confidence to speak, to share, to tell their stories without shame. It allows children to grow up proud of who they are, rooted in their own soil, not afraid of their own accent. It removes the fear of being judged or deemed uneducated simply because you can’t speak the Queen’s English. In doing so, we empower generations to come—to build, to preserve, to become.

We have everything we need to be who we want to be.