The Fields Before the Exam

The Sunday before my first ZIMSEC English exam remains etched in my memory (and I hope my memory serves me well). Sundays were usually peaceful—a day for light chores and preparing for the week ahead. But this one was different.

The week prior, the rains had blessed our fields, signaling the start of the farming season. By Sunday, the soil was ready for ploughing, and like any other day, I went through my usual routine. My Sundays typically ended with arranging my school uniform and helping with supper in our round hut, where we’d catch up on family matters.

But with the exam looming, Mama Shabba took the opportunity to emphasize its importance. “Failure is not an option,” she said sternly, her voice filled with conviction. Shabba believed deeply in education as a means to improve our lives. She’d even bought candles for my revision. While the paraffin lamp was our usual source of light, its soot made extended study sessions uncomfortable.

That night, I settled at my small desk, my books spread out before me. Without a clock, I relied on the moon to gauge the time. Its bright, full glow suggested it was around 8 pm when we retired for the night. I studied for about two hours, then decided to rest—knowing I’d have to plough the fields before school in the morning.

I was deep in sleep when a knock at the door jolted me awake. Groggy, I heard Mukoma Tafi, our helper, reminding me of our early morning plans. I stepped outside into the bright moonlight—it was so luminous you could spot a needle on the ground. We headed to the kraal to yoke the oxen, Braki and Majagi, for ploughing.

The fields were soaked from the rains, and the plough sliced easily through the earth. Mukoma Tafi took the plough while I led the oxen, who seemed unusually cooperative. Braki, known for its stubbornness, moved without a fuss. We completed the first dhunduru and moved to the second.

Something felt strange. The oxen were unnaturally calm, and the cool night air carried an eerie stillness. Then it hit me—I glanced at the sky. The moon was directly overhead, just as it had been when I’d gone to bed. Mukoma Tafi had woken me up at midnight or thereabouts —barely a few hours after I’d fallen asleep.

I remembered the old saying: Mombe hadzitinhwe husiku—oxen aren’t supposed to work at night. Perhaps this explained their unusual behavior. Yet, we carried on, finishing three dhundurus before the first rays of the sun peeked over the horizon.

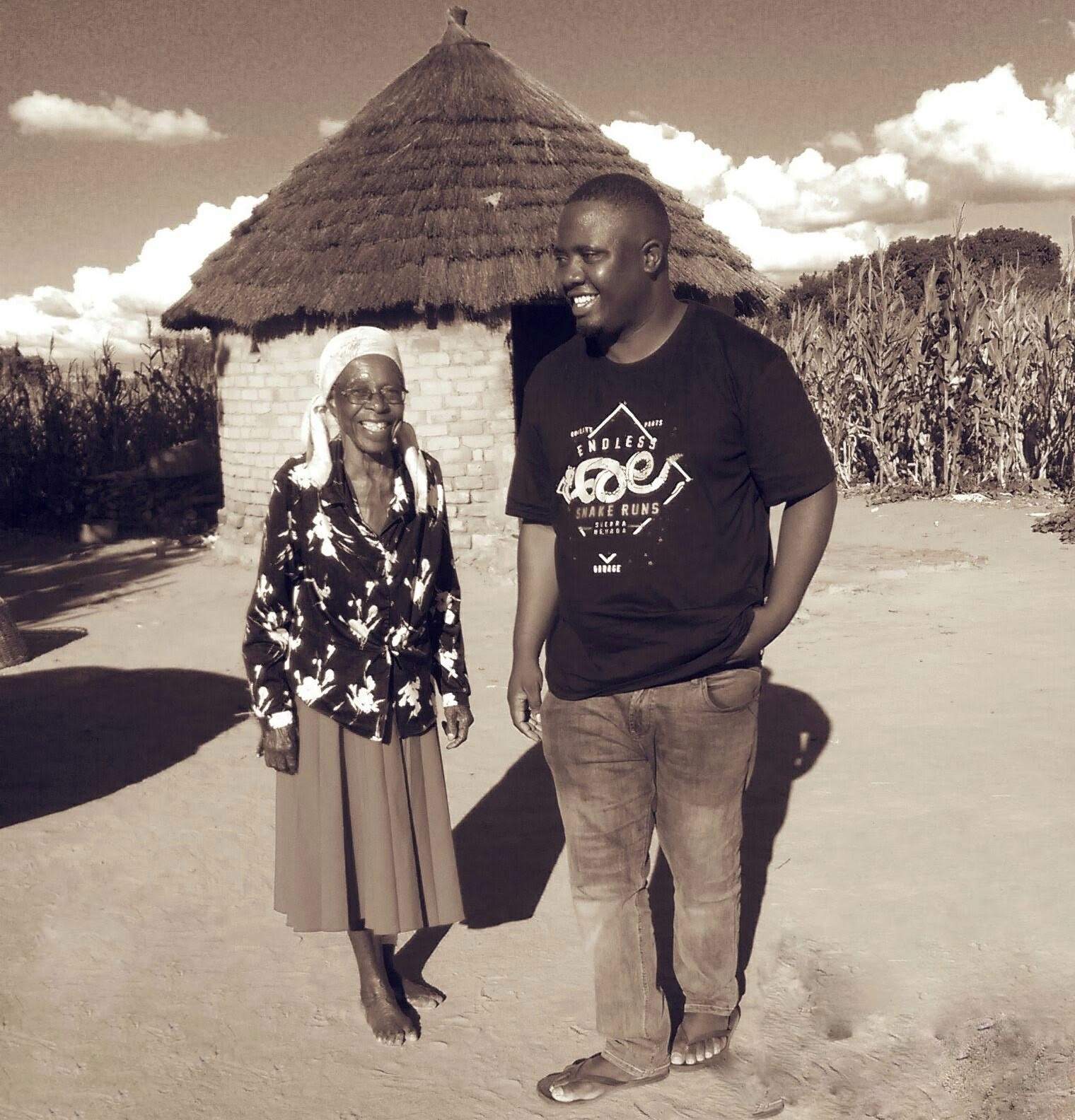

Just as we were unharnessing the oxen, Gogo Manhika appeared in the yard, her expression a mix of surprise and concern. “Nhai Tha, kana makutanga kutobopa mombe izvezvi, kuchikoro unoenda nguvai?” But we were done!

I rushed back to the house, took a hurried bath, and scarfed down the porridge Shabba had prepared. My school was three kilometers away, and I ran the entire distance, pacing myself to avoid exhaustion.

I arrived just in time, my heart pounding as the invigilator’s voice echoed through the classroom: “The time is exactly 9 o’clock. You may start writing.”

Looking back on that night, I realize it wasn’t just about preparing for an exam; it was about resilience, discipline, and the balance between responsibility and ambition. The experience taught me that success often demands sacrifices—whether it’s waking up in the dead of night to plough fields or pushing yourself to the limits for something that matters.

It also showed me the value of community and support. Shabba’s unwavering belief in education, Mukoma Tafi’s assistance, and even the calm demeanor of the oxen were reminders that we never walk our journeys alone.

Above all, that night instilled in me a deep appreciation for time—how easily it can be misjudged, how precious it is, and how wise use of it can lead to extraordinary outcomes. My journey from the fields to the exam desk that morning wasn’t just a testament to hard work but also a reflection of life’s delicate interplay of preparation, perseverance, and purpose.